Bilocation? Today it is possible. On the evening of June 8th I was in the Teatro Verdi in Florence, to see “Ferite a morte” by Serena Dandini, and at the same time in the Palazzo Vecchio, enjoying the conversation between Umberto Eco and Stefano Bartezzaghi. Miracles of the Internet, which has allowed me to enjoy both events taking place at the same time, thanks to the video made available a few hours after the event on the website of La Repubblica delle idee.

A review by Katia Riccardi arose in me great expectations: their conversation, entitled “Where do we start?”, has been focused on the concept of “incipit”, and in order to describe the meeting, the journalist chose to start with magic:

It was like watching two jugglers of words doing magic tricks. (1)

But in the article, magic was also the last concept cited:

Words are risky. They can change the course of events. Or just be nice to listen to, as they were tonight, as they danced in the hands of two magicians. (2)

Wow! – I said, the spirit of “a magician at ’La Repubblica delle Idee’” has also affected a lay journalist.

Exploring various literary incipit, Bartezzaghi focused on a fragment by Eco taken from the essay Postscript to “The Name of the Rose”:

For two years I have refused to answer idle questions on the order of […] «With which of the characters do you identify?» For God’s sake, with whom does the author identify? With the adverbs, obviously. (3)

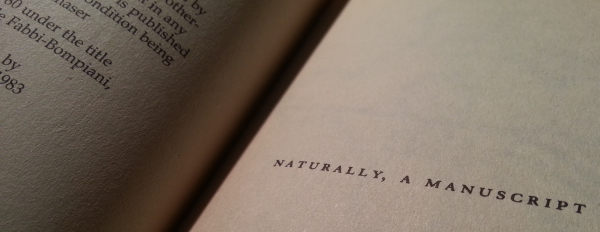

Bartezzaghi has pointed out that the first word that appears in The Name of the Rose is an adverb – “naturally” – and commented that probably Eco was not lying: he really identified himself with that word. Eco has confirmed amused.

The Name of the Rose opens with the title “Naturally, a manuscript.” For those who can grasp it, it is an ironic quotation. To pretend the discovery of a manuscript is an old trick, already used by the first Italian novelist – Alessandro Manzoni in his I promessi sposi (“The Betrothed”) – and after him by countless others. But if such a fiction in the 19th century could be proposed with carefree attitude, today there is only one way to offer it again without falling into kitsch: to add (symbolic) quotation marks, declaring the ironic frame and asking the reader to consciously adhere to the game. Since the entire Eco’s novel is full of accomplices winks, addressed to the aware reader, Bartezzaghi is justified in recognizing the author in the word “naturally”, the signal by which – since its opening – The Name of the Rose reveals its own nature and is addressed to those who are able to savor its intertextual taste.

On the left, Stefano Bartezzaghi. On the right, Umberto Eco.

The risk of falling into kitsch is not limited to literature: the artist who ignores what preceded him and revives something unaware of its origins, confines himself in the realm of amateurism. In my last book Te lo leggo nella mente (“I read it in your mind”) I explored this risk in “mentalism” – the branch of conjuring simulating in theatrical form the classic paranormal phenomena related to the powers of the mind.

In the past, mentalists used tricks to convince their audience of having superhuman abilities; today the same premise would be anachronistic. Acknowledging in modern spectators a shrewd intelligence, aware of the limits of human perception, great contemporary mentalists involve them in an exercise of the imagination: the game of “as if”. If Eco uses an adverb to wink at the cunning reader, also the mentalist invokes the complicity of the public through an ironic approach, encouraging a voluntary acceptance of the premise that paranormal phenomena are reproducible at will. In line with these assumptions, the performances offer an alternative version of the world, “as if” mind reading, clairvoyance, precognition, etc. were reality. With such an attitude, writers and mentalists relate to their fans by treating them as individuals aware and disenchanted, without invoking a “naive faith” in the reality of a manuscript or a paranormal dowry. But if many writers (such as Umberto Eco, Thomas Pynchon and Orhan Pamuk) have joined the “postmodernism”, stage magic has some difficulties to free itself from antiquated and out of fashion formulas. We have to look abroad to find artists capable of mastering “quotation marks” and adverbs: Max Maven and Derren Brown among mentalists, Penn&Teller and Leo Bassi among magicians.

It is unrealistic to expect a massive adherence to poetic so aware. Actually irony is a sophisticated weapon. Or – as the two authors commented in Florence during a lightning exchange:

Bartezzaghi: The irony is difficult.

Eco: …it selects!

1. Katia Riccardi, “Eco, Bartezzaghi e il mistero delle parole” in repubblica.it, 8.6.2013.

2. Ibidem.

3. Umberto Eco, Postscript to “The Name of the Rose”, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1984, p. 53

BY-NC-SA 4.0 • Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International