Making Heart and Mind work together is a goal toward which we are push by gurus, philosophers, religious leaders – and scientists, much more rarely. Balancing humanistic and scientific disciplines is a good way to harmonize the two hemispheres of the brain, logic and intuition, ingenuity and recklessness. Many people advocate the idea, but rarely they support it with a good practical example.

Here is a curious and compelling story, which begins on the French Riviera and ends in Stockholm. It involves flying saucers, an old IBM 1620 and a suitcase that goes around the world, showing how Mind and Heart can effectively cooperate.

It is 1954. Jean Cocteau and Aimé Michel are sipping a Pastis in villa Santo Sospir in Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat.

Park of villa Santo Sospir in Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat.

They talk about their common love: flying saucers. One of Cocteau’s portraits reminds of some constellations: joining together some points, he drew the picture of a face.

Jean Cocteau, “Orphée aux yeux Perles” (1950).

Being a good visionary, Cocteau looks at the portrait and sees a starry sky. And in the hand drawing the lines, the trajectory of an aircraft. It is the true vocation of the artist: pure intuition. His hypothesis: flying saucers communicate with us by drawing sketches in our skies.

Addressing his friend, Cocteau suggests:

You ought to see whether the objects move along certain lines, whether they are tracing out designs, or something like that. You might try to discover, for instance, whether their movements coincide with magnetic lines of force, or with any other lines in a significant way. (1)

Aimé Michel must translate Cocteau’s intuition in a testable hypothesis. It is the true vocation of science: to express an idea with mathematical symbols – the language spoken by Nature.

On September 24, 1954 in France there is a sudden wave of UFO sightings. Michel takes a globe and puts a pin on each of the cities involved (Bayonne, Lencouacq, Tulle, Ussel, Gelles and Vichy), realizing that they are aligned.

Hypothesis: UFO sightings recorded in a day are always arranged in a straight line.

Michel calls “orthoteny” the idea and describes it in his book Flying Saucers and the Straight-Line Mystery (2)

Jacques Vallée is also a scientist. With his knowledge of statistics, he is able to test the fascinating “orthotenic hypothesis”. In 1962, he collects hundreds of sightings in a rudimentary database running on IBM 1620.

Not only he detects alignments: he is aware that they may appear by chance. He compares their number with the one emerging when throwing catnip seeds on a geographical map. It is the true vocation of the statistician: detecting anomalies and assessing whether they are (or not) emerged by chance.

The numbers speak for themselves: orthotenic hypothesis does not hold. Falling in love with Cocteau’s vision is the first step. Admiring the rigor of the hypothesis proposed by Michel is the second step. Accepting that the hypothesis is wrong demands an uncommon detachment: it is a third (but not last) step.

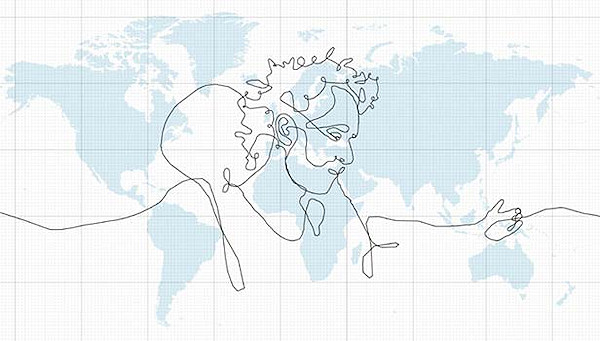

Cocteau’s intuition and Vallée’s skepticism are not mutually exclusive alternatives. The interaction between the two may be a huge creative stimulus. Erik Nordenankar grasps it immediately. The surrealist epic of a planet on which to draw, in no way is menaced by the demonstration that – no, aliens are not communicating with us. On the contrary, it is an invitation to roll up our sleeves and start to draw by ourselves. Nordenankar puts a GPS device in a suitcase and plans a series of shipments via DHL, sending it around the world long a twisted path crossing more than 60 different countries. Telling the story, the Swedish artist will say:

The suitcase became my pen, the world my paper. (3)

Tracing the route of the suitcase with GPS, within 55 days Nordenankar draws the biggest self-portrait ever:

But the true nature of Nordenankar is that of the trickster, whose true vocation is to confound, wreaking havoc and playing with chaos. His actual work is this video, documenting in detail the project:

As revealed by Matthew Moore in The Telegraph, nothing is real in the video. (4) No shipping, no involvement of DHL, no GPS device. Just a good idea, through which injecting Wonder and suggesting a unusual contamination. The performance of those who can take the fourth step.

Cocteau’s poetic intuition is irresistible. Michel frames it mathematically in the best way. Vallée shows its inconsistency with crystalline honesty. Only grasping the genius in each of them Nordenankar can go further, hacking reality and bringing to completion – through an elaborate illusion – an intuition too good to be false.

1. Aimé Michel, Flying Saucers and the Straight-Line Mystery, Criterion Books, New York 1958, p. 51.

2. Aimé Michel, Flying Saucers and the Straight-Line Mystery, Criterion Books, New York 1958

3. Erik Nordenankar, “Biggest Drawing in the World”, YouTube, 15.5.2008. Many thanks to Davide Brizio.

4. Matthew Moore, “’Biggest drawing in world’ revealed as hoax” The Telegraph, 27.5.2008.

BY-NC-SA 4.0 • Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International