Minneapolis, 29 September 1915. Thousands of people are gathered in front of the local newspaper building. There is a man hanging on his feet at the top of the palace. His eyes are out of the orbits. He breathes badly, being imprisoned in a straitjacket. The show is a strange struggle between an individual and what is choking him, but finally the man comes out victorious. He stretches out his arms and takes a deep breath, throwing away that horrible garment. A big applause explodes. Even this time, Harry Houdini is free (see the film of the escape).

Biographers will define him as the “America’s First Superhero” (1) , inquiring the reasons for his success. Why were his shows so mesmerizing? The answer is that Houdini was not a magician like the others: his escapes made him a symbol. The spectators projected on his straitjacket what made them feel oppressed. Like Christ on the cross, he took on those loads, “wearing them” and putting his life at risk. Playing with such primary emotions, all his victories sparked relief applauses that no rabbit from the hat would ever arouse. The sophisticated relationship between the wizard and his audience was thoroughly analyzed by Bernard C. Meyer, a psychoanalyst who devoted a book to the symbolic implications of Houdini’s escapes (2) ; an interesting reading, unfortunately missing of a crucial detail: acknowledging a meaning “behind” was an élitarian luxury.

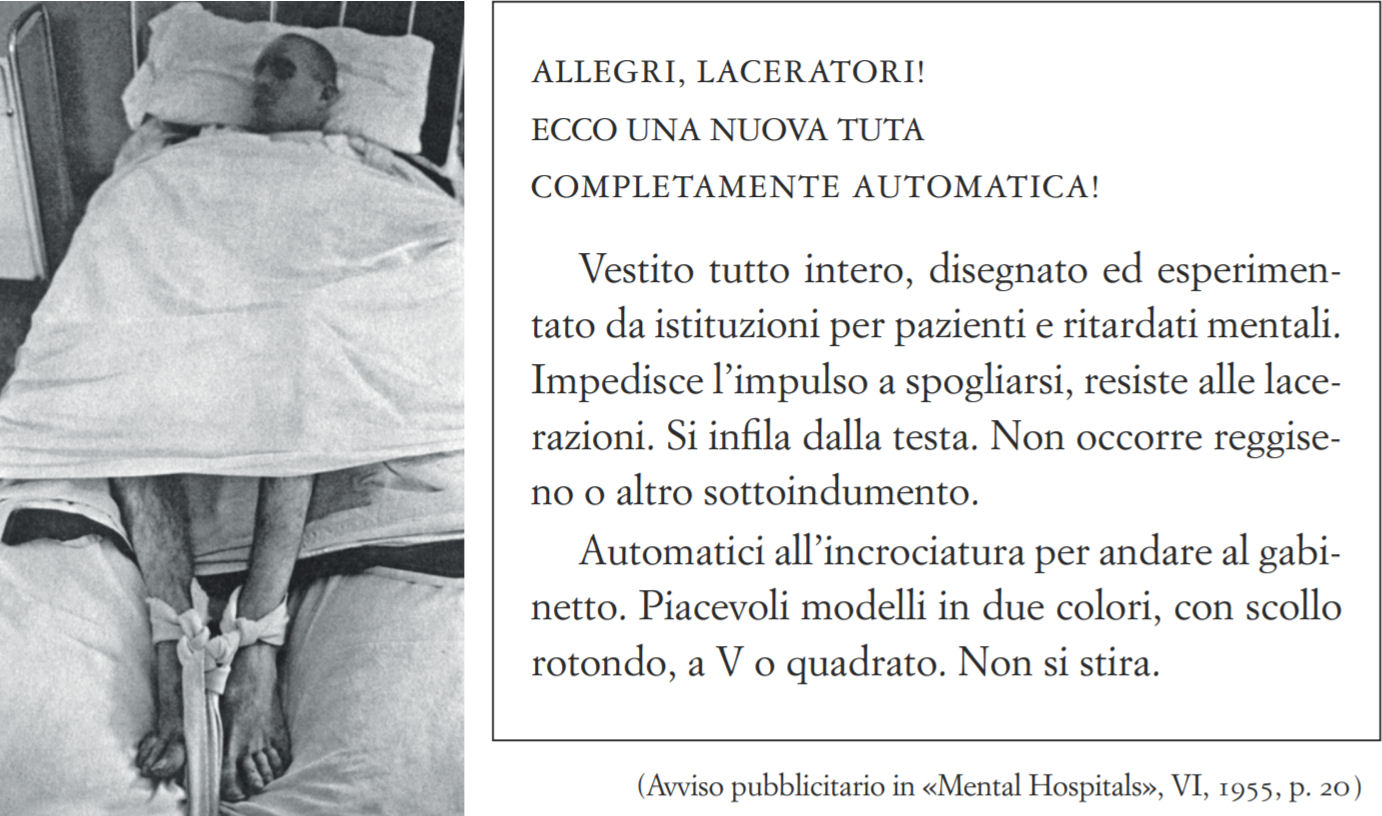

The streets were full of spectators ready to appreciate the metaphorical implications of Houdini’s escapes, but a whole crowd of excluded would have gladly celebrated their literal sense: the so-called “lunatics” who lived behind the bars without guilt, condemned to choke in straitjackets. They knew on their own skin the torments that the magician proposed during his shows: from the strips of leather tying to bed to the metal handcuff, from the chains to the strings blocking the wrists. For those who lived in a lunatic asylum, Houdini’s straitjacket was not the symbol of something else; each escape was the “literal” representation of the only thing that would have returned them the lost dignity. In psychiatric hospitals, those who tried to imitate him – the so-called “laceratori” – did not receive applause but hard punishments; to hold them, the magazine Mental Hospitals advertised a new, more durable straitjacket (chosen from two “pleasing models”).

HAPPY NEWS FOR LACERATORI!

HERE IS A NEW AND COMPLETELY AUTOMATIC OVERALLS!

Full dress, designed and tested by institutions for demented and lunatics. It inhibits the impulse to get naked, it resists to tearing. Worn from the head. No bra or undergarment needed.

Pushbutton below for corporal functions. Pleasing models in two colors, V- or square-necked. No need to iron.

Performing for those who lived in freedom, Houdini’s magic was born and died on a symbolic level, without giving impulse to any actual liberation; in Italy, between the 60s and 70s, the mission of bridging escapology from illusion to reality was promoted by a group of doctors and administrators who were able to make for real (and for everyone) what the magician only mimicked.

It was 1961 when Franco Basaglia, the new director of Gorizia’s mental asylum, entered in its building and was hit by an unbearable smell of “shit and death”. To illustrate the impression he had in front of a patient, the psychiatrist cited the description given by Jonathan Swift in 1733 of a “melancholic, wild, dirty, and sordid man, who was rummaging through his excretions and wallowed in his urine”, whose best part of the food “was made up of its own excrement, whose exhalations envelopped him.” His face “had a dirty yellow color that matched perfectly with that of his foods as certain insects that are born and raised among the excrement, taking on the color and the smell of the feces.” (3)

Like all psychiatric hospitals at the time, the site was a concentration camp whose patients were abandoned in inhuman conditions. Along with other colleagues, Basaglia inspired the birth of a radical psychiatric movement that rejected the half-measures: the mental asylum was not be reformed but destroyed; because actually it was not an institution designed to cure, being rather

a factory where the wreckage of the urban and peasantry proletariat is converted, through appropriate treatment, to “demented” officially recognized, labeled, offered to the healthy people with a warranty mark. This gives rise to the confirmation of their diversity and superiority, fueling the most vile and fierce prejudices and a form of racism that comes to separate and oppose those belonging to the same class. (4)

Franco Basaglia (1924-1980).

Without asking for any authorization, radical psychiatrists broke chains and straightjackets, opened dormitories, and released patients. To question the “magic” charisma making of the psychiatrist a figure of power, Basaglia scandalized many colleagues by removing his doctor’s shirt and confusing himself with the patients. Coming to Gorizia, it was difficult

for the newcomer [...] to accurately determine who the doctor was and who the patient was. This is perhaps a measure of the success of methods consciously used to level the authoritarian climate typical of most hospitals. If you remove the symbols of his position, it becomes really difficult for the doctor to resume, and retain, an authoritarian control over “the patient. (5)

Confusing in the eyes of the observer the boundary between normality and madness, Basaglia embodied the illusionistic play at the heart of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920).

Photo by The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920).

In the movie, the evil magician Caligari uses hypnosis to kill. Discovered and captured, the illusionist is locked in a forensic psychiatric asylum, tight in a straightjacket. When the story seems to be over, a twist questions the reality of what has been shown so far. The narrator turns out to be a fool who imagined everything: Caligari would be nothing but the director of the psychiatric hospital where the crazy storyteller is locked up.

Through zigzagging geometries and hallucinated backgrounds, Robert Wiene’s movie anticipated the Basaglia Revolution in the imaginary, leaving the final open and preventing the spectator from tracing a line that distinguished the asylum director from his patients.

Trusting the impossible was not enough: thanks to a day by day labor to achieve it, in 1978 Basaglia’s crazy dream came true and with the Law #180 Italy became the first (and only,so far) country in the world to abolish mental asylums.

Only the six forensic psychiatric hospitals (Opg, Ospedali psichiatrici giudiriari) instituted by the fascist penal code survived: truly Circles of Hell that combined the logic of prisons and that of lunatic asylums.

The Opg in Naples was then closed in 2008 and its premises abandoned. In view of the law that would abolish all of them, on 2 March 2015, the Neapolitan students of the Collettivo Autonomo Universitario occupied the former asylum to overturn it: the occupation marked the beginning of the Je so’ pazzo project (“I am crazy” in the dialect of Naples), a logical continuation of the Basaglia Revolution.

Thanks to the involvement of local associations and the contribution of hundreds of volunteers, for more than two years the former Opg has offered free medical, legal, after-school services, Italian lessons for foreigners, sports activities (from football to boxing, climbing to kung-fu), workshops, musicals, theatricals, has organized political campaigns (in support of migrants and against black work) and solidarity initiatives (one of which for the earthquake in central Italy). In parallel it conducts a careful job of restoring and renovating the premises, a work that so far has left unchanged the area where the Opg patients were imprisoned:

Cells of a few square meters, enclosed by heavy double-armored doors, floor-welded recessed beds, bars at every corridor, stacks of dirt uniformed brown uniforms and stacked shoes as in a concentration camp, of those sadly known in the 20th century. (6)

Details from the rooms of the former Opg of Naples. Photos by Mariano Tomatis, 27 December 2016.

The narrow horror rooms are today a museum denouncing the ruthless coercion of power against the weak.

The mural by Blu, decorating since March 2016 two facades of the former Opg, perfectly capture the two ingredients at the basis of the project’s magic: its cyclopean dimensions and the firm determination to break all the chains – literal and symbolic.

Visiting the former Opg on 27 December 2016, I was dazzled: Je so’ pazzo is transforming a place of death into a laboratory spreading powerful vital energies. In the eyes of a magician, “transmutations” of the genre are much more interesting than any alchemic smoke. By exposing yourself to its radiations, the contagion is immediate: you come out reloaded, having seen in person the concreteness of the proposals and the radicalism in opposing any form of oppression, authority and imprisonment through spaces of sharing, sociality and freedom.

The popular gym and the theater are made in the premises of the former Opg of Naples. Photos by Mariano Tomatis, 27 December 2016.

I regularly attend the world of illusionists, and they have often disappointed me with the use of the concept of “madness”: this category is often used to justify the carelessness and the lack of stylistic compactness of the performances; the empirical rule is simple: if you define “crazy, crazy, crazy” your magic show, it will crap. Few reach the psychiatric peaks of Yann Frisch, but to a magician asking me how to astonish through the madness, I would prescribe a visit to the former Opg of Naples. The secret ingredient of the people animating the Je so’ pazzo project is inspired by René Char’s magnificent exhortation:

Pathetic companions scarcely murmuring, going on with your lamp extinguished and giving back the jewels. A new mystery sings in your bones. Develop your legitimate strangeness. (7)

What is animating the Neapolitan project is the madness of those who give back the jewels – which is considered crazy: adopting values such as gratuity and sharing, Je so’ pazzo challenges the common logic, proves that a different world is possible and claims with pride the legitimacy of developing the strangeness of the Revolution. Assuming the perspective of madness as a privileged point of view, the group behind the project explains that

in a world where normality is made from unemployment, precariousness, discrimination of all kinds, to be crazy and dare to even occupy a former forensic lunatic asylum is an ideal opportunity to begin a fight in such a difficult city like Naples.

To let yourself be charmed by its magic, this is the perfect weekend: from 7 to 10 September Je so’ pazzo organises its 3rd Festival (visit the website). The former Opg will host debates, workshops, dinners, exhibitions, stands, theater performances and concerts: titled “Power to the People”, the Festival will be the occasion to share the wonders created by a community born from below in a radically antieconomic perspective, without the support of sponsors or political patrons.

“On the other hand,” they write, “what better place than a lunatic asylum to dream and do crazy things?”

1. Larry Sloman and Bill Kalush, The Secret Life of Houdini: The Making of America’s First Superhero, 2006.

2. Bernard C. Meyer, Houdini, a mind in chains. A psychoanalytic portrait, 1976.

3. Jonathan Swift cit. in Franco Basaglia and Franca Ongaro, Morire di classe, Einaudi, Torino 1969.

4. Associazione per la lotta contro le malattie mentali, La fabbrica della follia, Einaudi, Torino 1971.

5. Dennie Lynn Briggs, “Social Psychiatry in Great Britain” in American Journal of Nursing, n. 59, vol. 2, 1959, p. 218. The description refers to Dingleton hospital.

6. “Opg di Materdei: la concitata storia di un ospedale psichiatrico giudiziario”, Napolitan, 29.3.2015.

7. “Préface” in Michel Foucault, Folie et déraison. Histoire de la folie à l’age classique, Plon, Paris 1961.

BY-NC-SA 4.0 • Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International