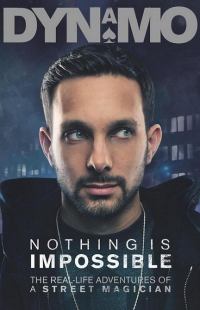

In his autobiography Nothing Is Impossible, English magician Dynamo describes magic as a tool to emancipate from playground bullying, racial abuse and a difficult family. This kind of narrative is repeatedly stressed in the book:

When you’re a kid life can seem tough; tougher for some than others. But the darkest of times can also be the most enlightening. When his late granddad showed him magic for the first time, Steven Frayne knew there was more to life than hiding from bullies.

In 1993 Dynamo is 11 years old, and Max Maven shows precognitive powers in his article “Febriferous”, by anticipating the path towards success of the young magician:

In this culture, the vast majority of those who engage in theatrical conjuring are males, typically beginning between ages seven and twelve. They are introduced to magic through an older friend or relative […] Why, at such a tender age, does their involvement build with such intensity? lt is because they have discovered a highly functional use for magic: Most beginning magicians immerse themselves in magic as a means of coping with some form of social, emotional and/or psychological maladjustment. […] The child has problems dealing with peers, parents, teachers, and so on. Knowing some conjuring secrets and cultivating the skills to perform them provides a crucial access to power for an often otherwise powerless youth. (1)

According to Maven, there is nothing inherently wrong with the scenario. But some implications should not be disregarded. In order to introduce them, Max offers an analogy:

Imagine that you and I are standing in a room, on the wall of which hangs a beautiful tapestry. Suddenly, you burst into fire. So, I quickly tear down the tapestry and wrap it around you, thus smothering the flames and saving your life. Now, is what I’ve done a bad thing? Of course not; in fact, it is morally commendable. In deed, by using the tapestry to rescue you from this predicament I have done something virtuous. However, this was not the principal purpose for which the tapestry was created, and although using it in this manner was clearly beneficial to you, it did not leave the tapestry in very good condition. (2)

Maven draws from this a ruthless lesson:

It is the same with magic. Using this art as a therapeutic tool can provide a figurative life-saving result, which is a fine thing. But such is not the principle purpose of magic; nor does it leave magic in very good condition. (3)

1. Max Maven, “Febriferous” in Magic, February 1993, page 14.

2. Ibidem.

3. Ibidem. The topic is also addressed in the next issue of Magic in Maven’s article “The shadow of your simile.”

BY-NC-SA 4.0 • Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International