During the Presentation Speech for the 2006 Nobel Prize in Literature, awarded to Orhan Pamuk, the Turkish writer was praised for his ability to recreate – in his novels – “credible” narrative places:

You have made your native city an indispensable literary territory, equal to Dostoyevsky’s St. Petersburg, Joyce’s Dublin or Proust’s Paris – a place where readers from all corners of the world can live another life, just as credible as their own. (1)

The emphasis on writer’s “credibility” accosts him to the figure of the magician. Anyone wishing to stage the impossible should, first of all, take care of the “credibility” of the performances: the demonstrations must seem inconceivable, yet completely transparent and authentic. In order to do it, tricks must be kept behind the curtains with care.

The credibility of Pamuk’s literary places emerges from subtle tricks. Beside the ability to evoke the atmosphere of Istanbul with skill, the writer has developed a peculiar style that gained him the adjective “postmodern”: an intricate blend of reality and fiction, achieved through sophisticated means.

If someone were to ask whether a word (hocus-pocus?), a story or a book can shape a tangible reality, his latest novel could be used as a spectacular response.

Some time ago Mario Baudino wrote about the fundraising being held at Edgbaston, Tolkien’s city. The city hosts a high neo-Gothic building, needing extensive repairs. For Lord of the Rings fans, it is a place of worship: Tolkien was inspired by its shape when he created the fortress of Isengard of the famous trilogy.

Baudino is puzzled about the issue:

So a ugly building does become worthy of the greatest interest, because (perhaps) it inspired a good book!? (2)

Hocus-pocus, Tolkien’s words are having a material impact on reality.

A few months ago – relatively speaking – I consulted for a similar operation: the restoration of a tiny shrine in Torre Canavese, Italy. The anonymous monument achieved some celebrity in 1997, when in my book The Holy Grail in Torre Canavese I described its main fresco as if it were the clue to a treasure hunt on the trail of the mythological cup of Christ. Just kidding, but – hocus-pocus! – the restoration was really done.

The conversation between Elena Stancarelli, Marco Ansaldo and Orhan Pamuk – hosted in “La Repubblica delle Idee” event – could not help but dwell on one of the most spectacular contamination between reality and fiction ever made, made in Istanbul by the Turkish writer: its “Museum of Innocence” is both a novel and a museum that confirms its truthfulness, in an ingenious borgesian game. Perplexed about this, the mathematician and writer Piergiorgio Odifreddi commented on Repubblica newspaper:

One question that comes to mind is whether and how a sensible person could spend his life in such an undertaking. And what all this may serve, beside gaining him the Nobel Prize. [...] Another question is what drives many of his readers, actual or potential, to go and visit this museum, paying 10 euro for observing real objects, whose only interest is that they have become fictitious, absolutely equal to all those who are in the other second-hand shops in Istanbul. (3)

When Odifreddi put the question directly to Pamuk, he received a response that emphasized the playful aspects of the operation:

Odifreddi: Are not you bothered [...] that some of your readers go on a pilgrimage to the museum, as readers of Dan Brown who follow the footsteps of Robert Langdon?

Pamuk: ...or like those of Tolstoy who go to St. Petersburg on Anna Karenina’s places? Not only it does not bother me, but I built the museum in order to allow it! There is a playful aspect, to create confusion by saying openly that the story is fiction, and at the same time in showing real objects that belong to it. (4)

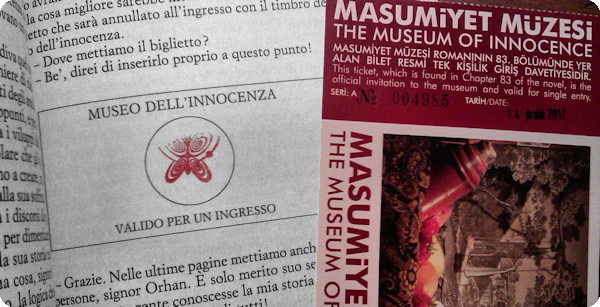

I visited the Museum of Innocence on December 14, saving the 10 euros thanks to a gift conceived by Pamuk: those who read the novel to the last page, come across a coupon printed directly on the book – a small circle that is stamped at the entrance with a butterfly-symbol of the place. Along with the stamp, the visitor receives a ticket for free.

The interplay between reality and fiction that reigns in the museum brought me back to mind the book by Michael Saler As If – Modern Enchantment and the Literary Prehistory of Virtual Reality (5) .

The Californian scholar offers an in-depth historical interpretation of games like the one by Pamuk, analyzing works and authors belonging to the literary movement of the “New Romance”. Founded as a reaction to the disenchantment of the world theorized by Max Weber, those authors produced works of fiction mimicking scientific treatises. Tolkien added maps and glossaries to his novels, creating alternative worlds whose internal coherence was strictly guaranteed. Lovecraft referred to specific physical concepts to establish terrifying cosmogonies, which had nothing to do with esoteric forces, but were based on electronuclear forces or uncontrolled chemical reactions. Conan Doyle endowed Sherlock Holmes with a hyper-rationality whose implications enabled him to perform stunts close to mind reading. These works were intended to wonder gratifying reason, without asking – in the modern and disenchanted reader – huge leaps of faith.

Literature of this kind can have unexpected consequences: what is astonishing has, often, the power to deceive those who can not distinguish clearly the boundaries between reality and fiction. Conan Doyle knew very well the problem: his existence was doubted by most naive readers, convinced that his detective was more “authentic” than him.

Saler identifies in “irony” the mean to achieve a “delight without delusion”, a state of wonder not resulting in deception. Pamuk totally masters its use.

His novel is full of winks to the aware reader. During a party, his protagonist encounters

...the chain-smocking twenty-three-year-old Orhan [Pamuk], [...] nervous and impatient, affecting a mocking smile. (6)

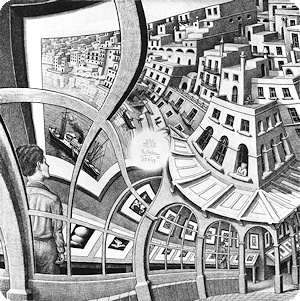

The mocking smile of the novelist is the minimum gap that reveals the game to those who are able to catch it. In later chapters, Pamuk interacts directly with the protagonist, shaping an Escherian narrative structure, characterized by intertwined frames.

Pamuk believes that the awareness of this game is a fundamental requirements of a modern reader, willing to enjoy a work of fiction in all its nuances. He has even dedicated to the theme his Norton Lectures in 2008, entitled “The Naïve and the Sentimental Novelist.”

The same interplay between reality and fiction is at the heart of the most refined forms of contemporary magic – particularly the one sensitive to the combination of “Magic & Meaning”; developed in contrast to the disenchantment of the world, conjuring offers theatrical experience in which the boundaries between reality and fiction are disrupted. In its more subtle incarnations, its purpose is what Coleridge attributed to the poetry of Wordsworth:

...to excite a feeling analogous to the supernatural, by awakening the mind’s attention from the lethargy of custom, and directing it to the loveliness and the wonders of the world before us. (7)

In the last part of the interview, Pamuk admits the double approach – aesthetic and political – used to conceive many of his writings. About the recent deforestation of a large park in the center of Istanbul, which has given rise to riots across the country, the writer still refers to the narratives: the Turks always meet near the trees, and they tied histories and fragments of their lives to each. Sawing trees means removing the memories and deleting stories. Another confirmation that words can create reality, but changing reality in turn may affect the stories. Or to put it with Alan Moore:

There are people. There are stories. The people think they shape the stories, but the reverse if often closer to the truth. Stories shape the world.

1. The Nobel Prize in Literature 2006 – Award Ceremony Speech

2. Mario Baudino, “La torre di Tolkien e i giallisti distratti” in La Stampa, 11.1.2013.

3. Piergiorgio Odifreddi, “Realtà e finzione”, 1.2.2013.

4. Piergiorgio Odifreddi, “Ero l’idiota di famiglia poi ho vinto il Nobel”, 21.2.2013.

5. Michael Saler, As If – Modern Enchantment and the Literary Prehistory of Virtual Reality, Oxford University Press, New York 2012.

6. Orhan Pamuk, The Museum of Innocence, Faber & Faber, London 2011, p. 160, translation by Maureen Freely.

7. Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Biographia literaria, 1817 (chapter 14).

BY-NC-SA 4.0 • Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International